Photo: Jeff Shea, 2022

Introduction

In the semi-arid grasslands of East Africa, an elusive creature moves with quiet grace— the Hirola antelope (Beatragus hunteri), a rare species so unique it stands as the last of its genus. The Hirola is not just another antelope; it’s a living relic, an ancient reminder of Africa’s evolutionary past. Yet today, this majestic animal teeters on the brink of extinction, with only a few hundred individuals remaining in the wild.

World Reserves’ initiative to create an International Hirola Reserve

World Reserves suggests to the world community, and particular to the governments of Kenya and Somalia, to expand the groundbreaking, already-successful predator-proof sanctuary at Ishaqbini by a factor of 20 to restore the pre-1970s population of >10,000. In 2024, World Reserves is meeting with local community and national government officials to further this idea.

Scientific and Visual Description

At first glance, the Hirola might resemble other African antelopes, but look closer, and you’ll notice a distinct beauty that sets it apart. Standing around 100–125 cm (39–49 inches) tall at the shoulder and weighing between 80 to 120 kg (176–265 lbs), Hirolas have a slender yet muscular frame, built for speed and endurance. Their coat is a sandy-brown, blending effortlessly into the dry savanna, with a slightly lighter underbelly.

What really catches the eye, however, are the markings on their face. The Hirola’s most striking feature is the pair of large, tear-shaped white markings that run from their eyes down to their muzzle. This has earned them the nickname “four-eyed antelope,” as these markings almost seem like a second set of eyes. Their elegant, slightly curved horns (present in both males and females) can grow up to 70 cm (27.5 inches) long, resembling those of hartebeests but with a gentler sweep.

Scientifically, the Hirola belongs to its own unique genus, Beatragus, making it a fascinating subject of study for evolutionary biologists. Genetic analysis has shown that the Hirola is the only surviving member of this lineage, which split from other antelopes millions of years ago.

The Name “Hirola”

The name “Hirola” comes from the Somali people, who inhabit the regions where the antelope is found. In Somali, “Hirola” translates roughly to “the peaceful one” or “the one who walks alone.” This reflects not only the animal’s calm demeanor but also its solitary nature. It was first scientifically described in the late 19th century by explorer and naturalist Colonel H.G.C. Swayne, though it was formally named Beatragus hunteri in honor of another British explorer, H.C.V. Hunter, who conducted extensive surveys in northern Kenya.

Special Markings and Adaptations

The Hirola’s facial markings are more than just cosmetic. Some experts believe these distinctive tear-shaped white patches may play a role in communication, helping individuals recognize one another from a distance in the vast, open plains. Their light coat color helps reflect the harsh sun of their environment, and their large, mobile ears allow them to detect predators from afar—an essential adaptation in the predator-rich savanna.

Population Decline and Causes

Once widespread across northeastern Kenya and southern Somalia, the Hirola population has suffered a catastrophic decline over the last century. As of 2023, it is estimated that fewer than 500 individuals remain in the wild, making it one of the world’s most critically endangered mammals.

Several factors have contributed to this alarming decline:

- Habitat Loss: As human populations in Kenya and Somalia have grown, Hirola habitat has been converted to farmland and grazing land for livestock. This has fragmented the Hirola’s natural range and degraded their grassland ecosystem.

- Drought: The semi-arid environment of the Hirola’s habitat is prone to prolonged droughts, which have become more frequent due to climate change. Drought reduces the availability of food and water, forcing Hirola to compete with domestic livestock for resources.

- Predation: Hirola antelopes are preyed upon by some of Africa’s most fearsome carnivores, including lions, cheetahs, and African wild dogs. Normally, they could escape predators by outrunning them, but with their numbers so low and their habitat so fragmented, they’ve become increasingly vulnerable.

- Disease: Outbreaks of diseases like rinderpest have historically decimated Hirola populations, particularly in the 1980s. While rinderpest has since been eradicated, other diseases, exacerbated by contact with livestock, continue to pose a threat.

- Poaching: While Hirola are not a primary target for poachers, they are sometimes caught in snares meant for other animals, such as bushmeat species. The stress of human activity in their habitat further drives them into ever-smaller territories.

Habitat and Feeding

The Hirola’s home is the open, grassy plains and savannas of the Horn of Africa, primarily in northeastern Kenya. They prefer semi-arid, lightly wooded regions with abundant grass cover, where they can graze on a variety of grasses and shrubs. Their diet consists mainly of fresh shoots and leaves, especially after rains when the grass is most nutritious.

Hirola are incredibly water-efficient and can survive long periods without drinking. This allows them to inhabit areas far from permanent water sources. However, during extreme droughts, they are forced to migrate in search of water, which can expose them to predators and conflicts with humans and livestock.

Predators and Social Behavior

In terms of predators, Hirola antelopes have a formidable lineup of threats. Lions, cheetahs, and African wild dogs are their primary predators, though young Hirola may also fall prey to leopards and even large eagles. The Hirola’s best defense is its speed and agility. When alarmed, they can sprint up to 50 mph (80 kph) to escape predators, often performing a series of zig-zag leaps to evade capture.

Hirola are social animals, though they tend to form smaller herds compared to other antelope species. Herds usually consist of 10 to 20 individuals, led by a dominant male. Females and their young form the core of the herd, while males tend to be more territorial. Young males are often pushed out of their natal herd and must establish their own territories.

Conservation Efforts: What Can Be Done to Save the Hirola?

The battle to save the Hirola from extinction is a race against time. Several conservation initiatives have been launched, focusing on habitat protection, anti-poaching measures, and community involvement.

- Hirola Conservation Initiatives (HCI): We are committed to supporting the livelihoods of the communities living in areas where the critically endangered Hirola antelope exists, as 90% of their economy relies on livestock. Through a targeted vaccination program, we aim to protect not only the livestock but also safeguard the Hirola population from the risk of zoonotic and endemic diseases that can be transmitted between wildlife and domestic animals. This initiative will enhance both community well-being and conservation efforts by reducing disease outbreaks that threaten the survival of this iconic species and the livestock-dependent communities.

- Translocations: In a bid to expand the Hirola’s range, conservationists have undertaken translocation efforts, moving small groups of Hirola to protected areas, such as Tsavo East National Park in Kenya. This has helped create a backup population, away from the threats faced in their native range.

- Community Engagement: Local communities play a crucial role in Hirola conservation. Involving pastoralists in the management of grazing areas ensures that there is enough food for both livestock and wildlife. Education programs have also been launched to raise awareness about the importance of the Hirola and the benefits of protecting it.

- Habitat Restoration: With much of the Hirola’s habitat lost or degraded, efforts to restore native grasslands are key to their survival. This involves removing invasive plant species, controlling grazing, and replanting native grasses that provide essential food and cover for Hirola.

Suggested plan to facilitate population increase to pre-1970s levels of > 10,000

The Hirola Antelope is native only to Kenya and Somalia. The current population of the Hirola is between 400 and 500. In addition to concern over its possible extinction, the loss of the Hirola species will also be the demise of the entire genus Beatragus, as the Hirola is its only living member, making this program vitally important.

The overall objective of creating Hirola International Reserve is to increase the population of Beatragus hunteri to pre-1970s levels of at least 10,000. “The natural population in the 1970s was likely to number 10,000–15,000 individuals but there was an 85–90% decline between 1983 and 1985.” (King, 2011).

This effort requires the cooperation of the local community. Since the lives of the nomadic people of northeastern Kenya revolve around their livestock, assisting them in improving their way of life – particularly in facilitating water for their cattle as well as improving access to human medical services – is the way to win their hearts and minds. The local peoples’ full support is required to facilitate general approval for use of lands to create predator-free sanctuaries to conserve and preserve the critically endangered Hirola species. The Hirola sanctuary at Ishaqbini in Garissa County has proven that eliminating natural predators (lions, hyenas, cheetahs), as well protecting Hirola against human predators, directly resulted in a nearly four-fold increase in the Hirola population over a period of nine years.

We assume, because of the dramatic reduction of Hirola in the wild, that the project will not meet its targets unless we construct predator-proof sanctuaries in the style of Ishaqbini.

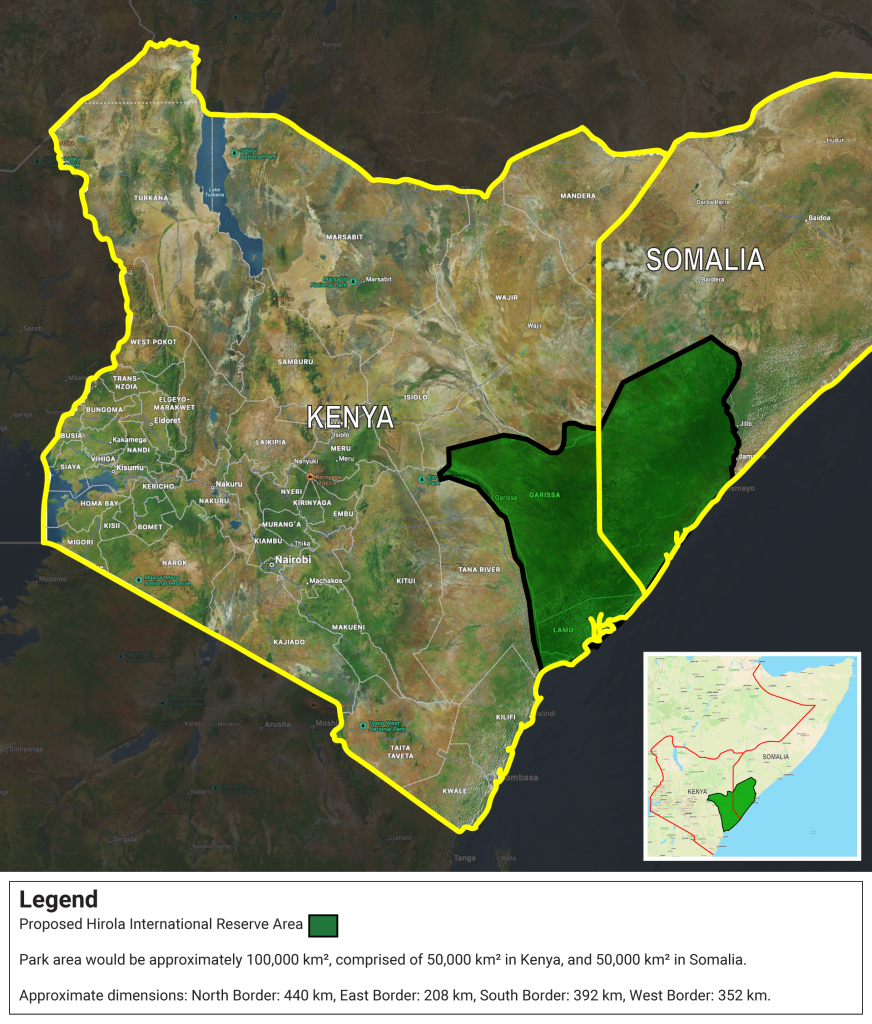

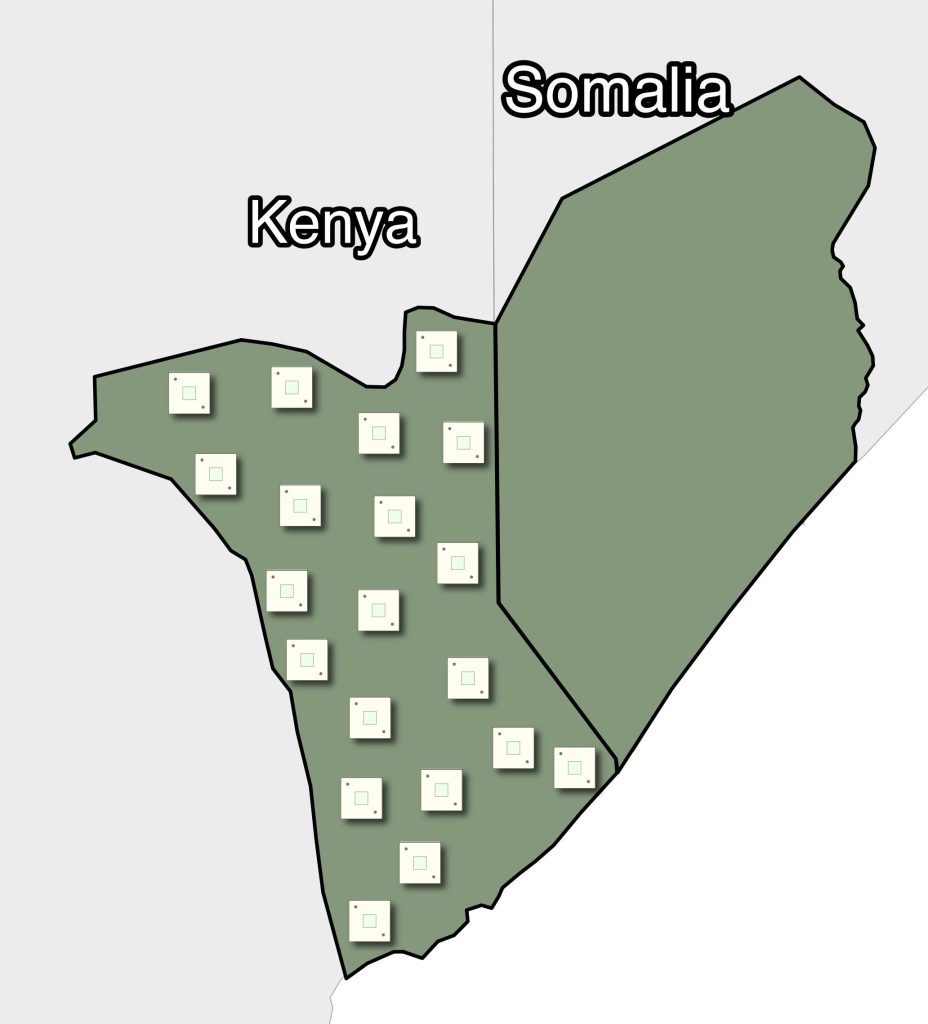

Defining the boundaries of the International Hirola Reserve and assessing necessary size

In order to restore the Hirola population to 10,000, we envision a reserve within Kenya of approximately 225 kilometers square and the same-sized reserve within Somalia. This would be in total 225 km x 444 km, or 100,000 km2. It would be expected that Somalia would support the project with a commitment to earmark a similar amount of land and resources. In short, this paper proposes a reserve of 50,000 km2 of land within Kenya.

Our estimate is that 100,000 square kilometers of territory is necessary to accommodate 10,000 Hirola (or 1 Hirola for every 10 km2). This is deduced from the following documented facts:

- “The size of a nursery herd’s home range varies from 26 to 164.7 square kilometres (10.0 to 63.6 sq mi) with a mean size of 81.5 square kilometres (31.5 sq mi).” (Andanje, 2002.)

- “Nursery herds number from 5 to 40 although the mean herd size is 7-9. They are usually accompanied by an adult male.” (Kingdon (1982) & Andanje (1995)).

- “As of 2014, a 23 km2 predator-proof fenced sanctuary has been constructed at Ishaqbini and a founding population of 48 hirola is breeding well within the sanctuary. (King, et al. (2014)). (Note: There is conflicting information about the size of Ishaqbini sanctuary.)

- “Adult males attempt to secure a territory on good pasture. These territories are up to 7 square kilometres (2.7 sq mi).” (Bunderson, W. T. (1985))

Calculations: Mean nursery herd home range 81.5 square kilometers, mean size of nursery herds = 8. Therefore, it is reasonable to estimate 10 square kilometers required for 1 Hirola in the wild. Ishaqbini was 23 km2, but now it is purported to be 43 km2. A maximum capacity of 183 was reached inside that 43 km2; therefore, there were approximately 4 Hirola per km2. In other words, the population density inside the predator-free sanctuary was 40 times the natural population density of Hirola living in the wild. The expected population in an area of 10 km2 in the wild is 1, whereas in a 10 km2 predator-proof sanctuary, 40 Hirola can co-exist.

The Ishaqbini Sanctuary reached maximum capacity with roughly 183 Hirola in an area of 43 km2. (Hussein, personal communication, 2024.) For the purposes of this paper, we will assume an upper limit of 5 Hirola can co-exist per km2. Further note that since our suggestion is to split this distribution equally between Kenya and Somalia, our target is 5000 Hirola in Kenya and 5000 Hirola in Somalia.

Given a target population of 10,000 Hirola in the wild, we estimate (10,000/0.1 Hirola per km2 =) 100,000 km2 of land required; but in captivity, 10,000 Hirola can co-exist in (10,000/5 Hirola/km2 =) 2000 km2. Our suggested plan is that when the maximum capacity of a sanctuary is reached (250 Hirola in 50 km2), the Hirola would gradually be released while the sanctuary would remain as a breeding ground.

Development of the proposed Hirola International Reserve would be in phases. For the remainder of this paper, we will focus only on the 50,000 km2 proposed for Kenya and building up the population of the Hirola within Kenya to 5000.

Phase 1 for Kenyan HIR

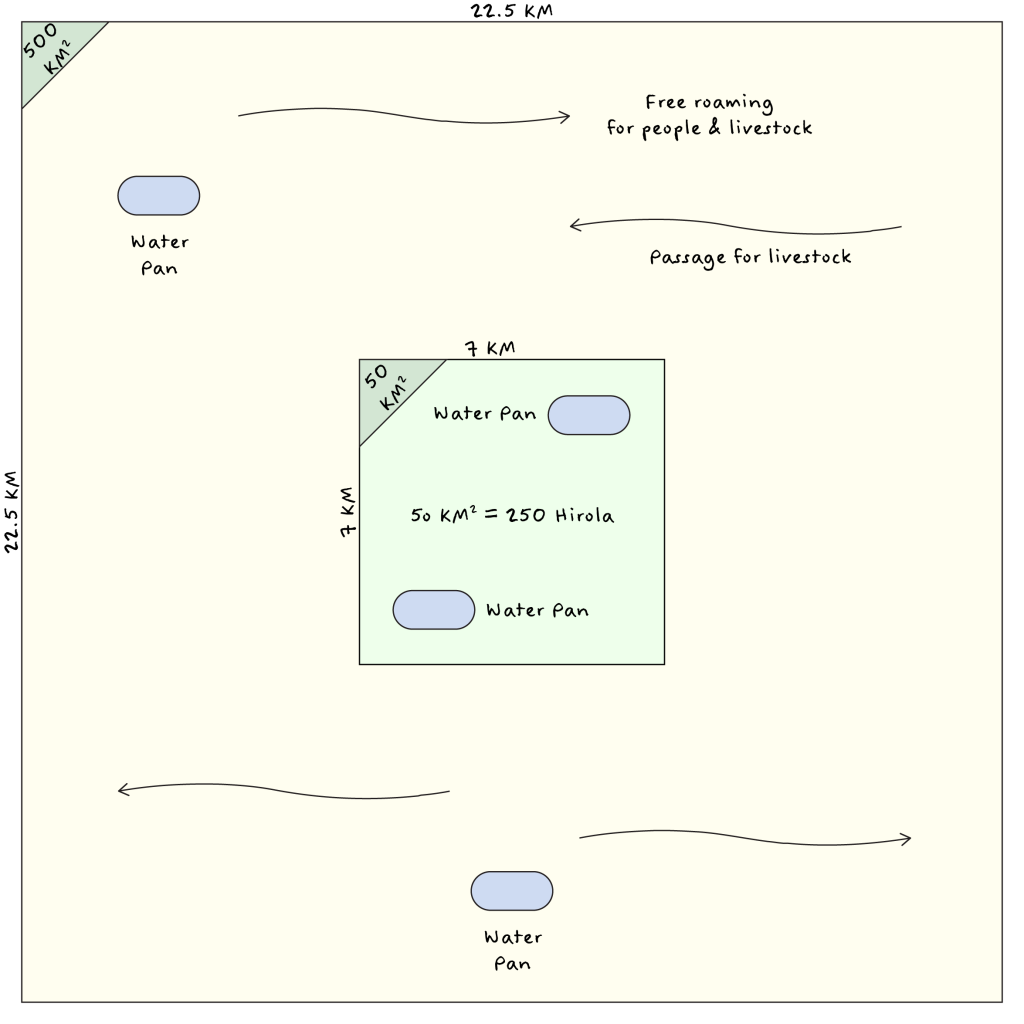

Phase 1’s mission will be to build up the population of the Hirola within Kenya to 5000 through the use of 20 sanctuaries, each approximately 7 km x 7 km (=50 km2), and each positioned within a “parcel” of 500 km2. (Note: actual size at 22.5 km x 22.km is 506.25 km2, rounded to 500 km for simplicity.)

Detail of an example parcel is shown below:

This is only an example, and the actual positioning of the sanctuary within a parcel could be designed by a landscape architect, and each could be different, depending on what was appropriate for the surroundings.

- Each sanctuary will occupy a “parcel” 10 x its size. A 50 km2 predator-free sanctuary would sit in a parcel of 500 km2. The parcel would occupy land equivalent to 22.5 km long and 22.5 km wide (= 500 km2), while the sanctuary itself would be equivalent to 7 km long x 7 km wide (= 50 km2). The balance of the land will be left “free” is to ensure low impact on the natural ecology and allow local people to live and move freely.

- One parcel/sanctuary would be potential home to a population of 250 Hirola.

- Each parcel would have one 50 km2 sanctuary.

- Once a sanctuary is approved by the local community and the funding is in place, actual construction should take approximately two years.

- Cost to build sanctuary: approximately $2 million (2024 dollars) for fence, electrified fence and other infrastructure.

- Within each parcel we will drill four bore holes, two of which would be inside the sanctuary itself. This will provide water for both the Hirola inside the sanctuary (2 bore holes) and the livestock outside (2 bore holes).

- Cost per bore hole: $15,000, x 4 = $60,000.

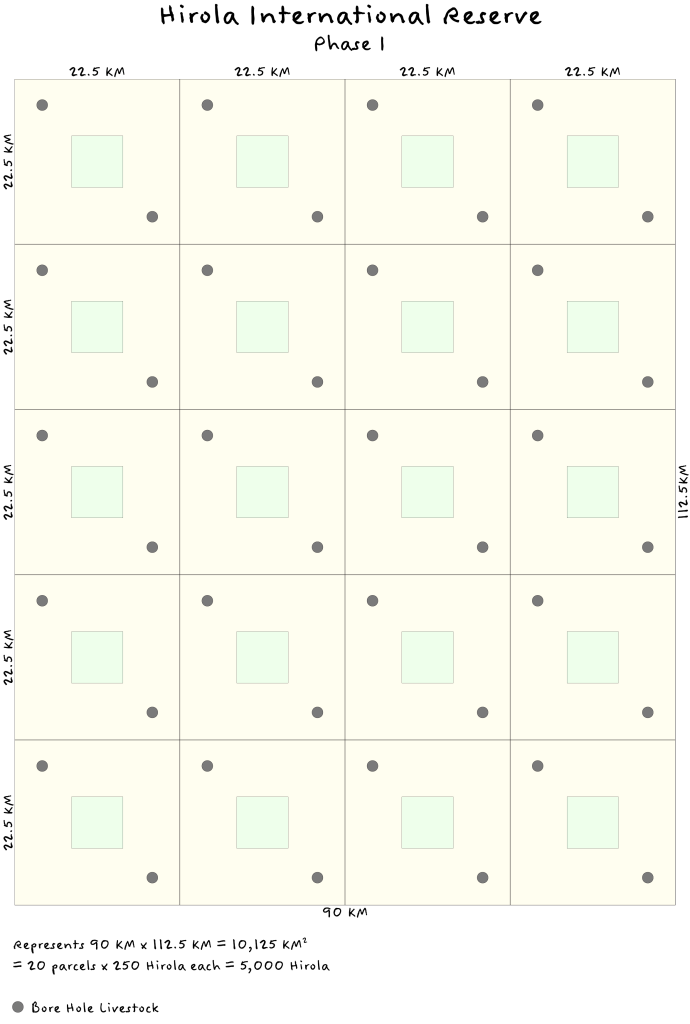

- At 250 Hirola per sanctuary, we plan to build out 20 parcels, to eventually reach a population of 5000 Hirola in Kenya.

- We figure to expect additional costs $500,000 per parcel.

- Total costs for parcel/sanctuary infrastructure, not including lodges, staffing, etc.: $2,560,000 per parcel x 20 parcels = $51.2 million USD.

How parcels would fit into the overall landscape of the proposed Hirola International Reserve.

The following illustration is conceptual, and it is not intended that all parcels are arranged in a grid as shown below. The idea is to show that 20 such parcels could be breeding grounds for Kenya’s quota of 5000 Hirola. In reality, the 20 parcels would be placed in a more imaginative way, appropriate to the circumstances.

Key objectives of Phase 1

Providing open space between sanctuaries for free movement, allowing virtually unrestricted access of local populations (both human and animal) to continue age-old traditions of movement.

Protecting Hirola in 20 manageably sized sanctuaries.

Phase 2

At the close of Phase 1, we hope to accomplish having 20 Hirola sanctuaries in the style and roughly the size of Ishaqbini.

Even though we have demonstrated that 5000 Hirola in relative captivity can survive in a space of 1000 km2 (the space inside the actual sanctuaries is 50 km2 x 20 sanctuaries = 1,000 km2), this does not reflect natural distribution of 10 km2 per Hirola, which necessitates 50,000 km2 to support 5000 Hirola in Kenya in the wild.

Phase 1 focuses on increasing the Hirola population. Phase 2 focuses on setting up a permanent infrastructure for rangers, local staffing, scientists, students, eco-tourists and locals associated with HIR. This will not only be to reinforce the security of the Hirola – it can also bring revenue, jobs and prestige to northeastern Kenya.

In parallel while building of sanctuaries and water holes of Phase 1, Hirola International Reserve (HIR) can begin to work on Phase 2, including the introduction of lodges. We suggest that with each of the 20 sanctuaries, we erect some type of lodge and/or housing. These will serve as hubs for coordination of activities and as living quarters of rangers and construction workers . Lodges can serve as centers for local education and international visitors, including scientists, eco-tourists and international students.

Artist’s conception of Lodge Zoo

We propose that Kenya implement “lodge zoos”, where, adjacent to the lodge, there is an open area where animals will be free to live and graze, yet visible to tourists and scientists. The following indigenous animals could be inhabitants of these fenced yet open spaces: hirola, elephants, African Wild Dog, eland, oryx, buffalo, topi, Tana Mangabey, Tana Red Colobus Monkey, reticulated giraffe (including the white rare giraffe), lion, zebra, ostrich, warthog, lesser kudu, gerenuk and dik-dik. Cheetah, leopard and hyena would have to be separated but might also be inhabitants of the complex.

Artist’s conception of Educational Center

Benefits

It should be kept in mind that along with investment, there will be direct, tangible benefits to the local population, the wildlife (not just Hirola) and to Kenya as a country for its far-reaching, visionary treatment of a knotty but not uncommon phenomenon (possible extinction of a species). Kenya would be doing a service to the world, since similar problems exist in many of the world’s nations.

Summary of ways the Hirola International Reserve can create jobs.

- Rangers.

- Managers.

- Drivers.

- Vaccinations.

- Building predator-free sanctuaries (e.g., Ishaqbini).

- Drilling bore holes for water in the sanctuaries.

- Drilling bore holes for water outside the sanctuaries for nomadic people.

- Creating ponds/waterholes for feeding of livestock.

- Building lodges.

- Employment at lodges.

- Tourist revenue, and influx of visitors including university-associated international cooperation for scientific study (including internship programs).

- Educational programs focusing on: a. local ecology, b. maintaining natural way of life, c. studying & documenting flora and fauna, d. anthropological studies.

- Additional related programs, such as once-annual tree planting projects.

- Cross national education and study.

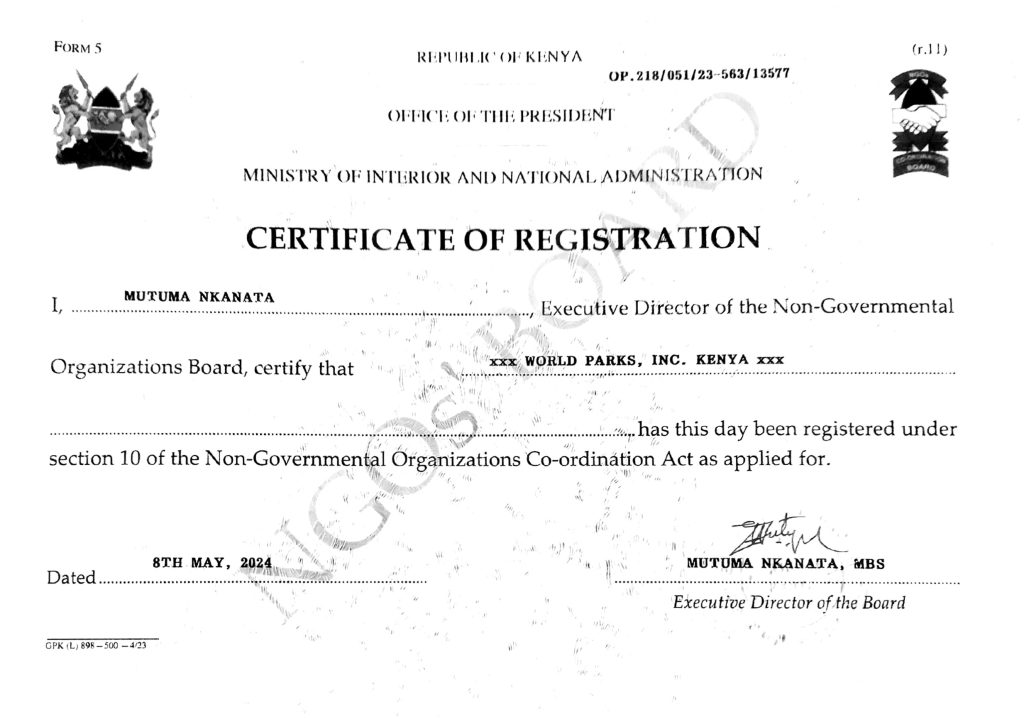

World Parks Kenya

The proposed Hirola International Reserve is a project under the auspices of World Parks Kenya, an NGO registered in the Republic of Kenya, registration number OP. 218/051/23-563/13577 under the Office Of The President, under the Ministry Of Interior and National Administration.

The constituency of the Board of Directors of World Parks Kenya is as follows:

- Chairman – Julius Kipgnitech

- Director – Tom Sipul

- Director – Jeff Shea (World Reserves, USA)

- Director – Jane Akumu Nguka

- Director – Mohamed Ahmed Kheri

References;

- King, J., Craig, I., Andanje, S. and Musyoki, C. (2011) They Came, They Saw, They Counted, SWARA, 34: (2).

- Andanje, S. A. (2002) Factors limiting the abundance and distribution of hirola (Beatragus hunteri) in Kenya[permanent dead link]. PhD thesis: University of Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK

- Kingdon, J. (1982) East African Mammals. An Atlas of Evolution in Africa. Vol. IIID. Bovids. Academic Press: New York. 395- 746; Andanje, S. A. and Goeltenboth, P. (1995) Aspects of the Ecology of the Hunter’s Antelope or Hirola (Beatrugus hunteri, Sclater, 1889) in Tsavo East National Park, Kenya. Kenya Wildlife Service, Research and Planning Unit: Nairobi, Kenya; Bunderson, W. T. (1985) The Population, Distribution and Habitat Preferences of the Hunter’s Antelope Damaliscus hunteri in north-east Kenya. In litt. to J. Williamson, WCMC: Cambridge, UK. 13; Andanje, S. A. and Ottichilo, W. K. (1999) Population status and feeding habits of the translocated sub-population of Hunter’s antelope or hirola (Beatragus hunteri, Sclater, 1889) in Tsavo East National Park, Kenya. African Journal of Ecology, 37: (1) 38–48.

- King, J., Craig, I., Golicha, M., Sheikh, M., Lesowapir, S., Letoiye, D., Lesimirdana, D., and Worden, J. (2014) Status of hirola in Ishaqbini community conservancy. Northern Rangelands Trust and Ishaqbini Hirola Community Conservancy, Kenya.

- Bunderson, W. T. (1985) The Population, Distribution and Habitat Preferences of the Hunter’s Antelope Damaliscus hunteri in north-east Kenya. In litt. to J. Williamson, WCMC: Cambridge, UK. 13.